Rob Smith, in one of his Literacy Shed blog posts writes:

As I have said in my previous posts – I am not opposed to testing. I do not like high stakes testing and how the tests are used to judge teachers and schools.

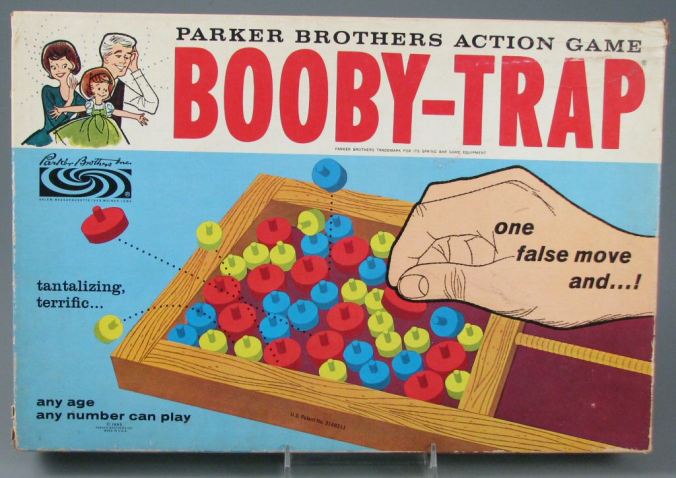

However, I am against tests that are filled with ‘booby traps’ and questions designed to confound and bamboozle young children. I call them ‘trick questions,’ but it has been pointed out to me that they are not trick questions just difficult ones.

I have come across a few sample SPAG test questions recently that have made me think.

The first from the KS1 Sample test.

Circle the verbs in the sentence below.

Yesterday was the school sports day and Jo wore her new running shoes.

‘Booby traps’ are what test designers call ‘distractors’. These are plausible, but incorrect answers, often used in multiple choice tests. Having distractors is a way for a test to distinguish the more able candidates from the less able ones, which is what all tests need to do.

In the example that Rob quotes the ‘booby traps’ are the past tense verb wore and the word running before the noun shoes.

I think we can be brief about the first of these. Granted, wore is an irregular verb, i.e. it is not formed using the regular past tense inflection -ed, and hence less easily recognisable as a verb, but it is not unreasonable to have such distractors in the test, as they can be used to probe the depth of knowledge that a particular child has of the grammar of verbs.

The second booby trap is indeed questionable. Which word class does running belong to? In the test designers’ view running is an adjective, since it occurs before a noun. They intended the item to ‘catch out’ children who think it is a verb. I agree with Rob that this is not a reasonable distractor, because it is highly debatable whether or not running is an adjective in this case. In my view it is more reasonably labelled as a verb. Why? Well, first of all, running is a present participle of the verb run. Secondly, if it were an adjective, why doesn’t it behave like an adjective in other respects? We can’t say, for example, *the very running shoes (compare the very big house) not can we say *the more running shoes (compare the more interesting problem). The fact that running occurs before a noun is neither a necessary nor a sufficient reason for labelling it as an adjective. Now, not all grammar books would agree with this. We’re dealing with a problematic area of grammar that linguists have discussed extensively (for a summary, see my book Syntactic gradience: the nature of grammatical indeterminacy). For this reason it would not be fair to have this kind of distractor in tests for children.

Having said that, to my knowledge the sample test in which this item occurs had not been scrutinised by a Department for Education Test Review Group. As a member of one of these groups I can confidently say that unfair distractors such as the one discussed above are weeded out prior to publication.

I’m not sure. Obviously one has to agree that ‘running’ is the present participle, and it can’t, as you point out, be modified: but the word obviously pre-modifies ‘shoes’, More importantly, I’d say that one would need to distinguish between the syntax of the sentence above and one from an imaginary story where the shoes take on a life of their own and escape: “Jo couldn’t catch up with the running shoes.” Or, if that’s unbelievable, how about “She watched the rapidly climbing man”? There, the adverb indicates that ‘climbing’ is acting as a verb: it’s something the man is doing, and one could rephrase: “She watched the man who was climbing rapidly.” In the ‘booby trap’ example, the shoes aren’t running.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful-as-ever comments, Sue.

You write: “…but the word obviously pre-modifies ‘shoes’ ” This is true, but it’s not enough to make ‘running’ an adjective. Nouns can modify nouns, as in the ‘key strategy’. We don’t analyse them as adjectives here.

I agree that in ‘the climbing man’ the word ‘climbing’ is clearly a verb, because it can be preceded by an adverb. In the example from the test it is hard to insert an adverb, and that’s because, as you say, the shoes aren’t running. Nevertheless, this still does not persuade me to see ‘running’ as an adjective. Perhaps it’s best to regard ‘running shoes’ as a compound noun here, as we would with ‘walking shoes’.

Overall though, my main point stands: it’s exactly because grammarians disagree about the status of a word like ‘running’ in ‘running shoes’ that such examples should not be used in tests.

LikeLike

Isn’t ‘running’ in this instance a gerund? As such it’s a noun pre-modifying another noun, as you suggested is possible. It’s a noun formed from a present participle verb, acting ‘adjectivally’. Sounds like a booby trap to me!

LikeLike

Dear Tom,

It’s impossible to say whether a form ending in -ing occurring on its own is a gerund, as its classification depends on the company it keeps. In the phrase ‘walking shoes’ it’s not possible to modify ‘walking’ as in, for example, ‘quickly walking shoes’. This would be evidence that ‘walking’ is a verb (cf. ‘quickly ticking watch’). However, it’s also hard to modify it such that it’s clearly a noun, hence my proposal that ‘walking shoes’ is probably best regarded as a compound noun. (See also Steven’s interesting comments below on ‘run vests’.) Personally I prefer avoiding the label ‘gerund’. Here’s the entry on ‘gerund’ in the Oxford Dictionary of English Grammar (Aarts, Chalker and Weiner; second edition, 2014):

gerund

Traditionally the gerund is the -ing form of a verb when used in a noun-like way, as in ‘The playing of ball games is prohibited’, in contrast to the same form used as a participle, e.g. ‘Everyone was playing ball games’. Sometimes called verbal noun. Both the term gerund, from Latin grammar, and the term verbal noun are out of favour among some modern grammarians. The noun-like and verb-like properties of the -ing form are on a cline. Consider the following examples:

He is smoking twenty cigarettes a day

The smoking of cigarettes is forbidden here

My smoking twenty cigarettes a day annoys them

In the first example ‘smoking’ is clearly a verb, by virtue of licensing a direct object (twenty cigarettes). In the second example ‘smoking’ is a noun because it is preceded by the definite article, and because it takes a prepositional phrase as its complement (of cigarettes). In the third example ‘smoking’ is noun-like in being preceded by the possessive pronoun ‘my’ (analysed in some grammars as a determiner), and in functioning as the head of the phrase ‘my smoking twenty cigarettes a day’, which occurs in a noun phrase position as the subject of the sentence. However, it is verb-like in taking a direct object, and in retaining verbal meaning.

When a word in -ing derived from a verb inflects for plural and lacks verbal meaning, it is considered to be a noun (e.g. these delightful drawings).

LikeLike

I know the tests themselves go through a pretty rigorous process of checking (you’re involved, Bas, so I wouldn’t expect any less!) but many of the resources and tests that teachers are using don’t. Some of the stuff I’ve seen, in the form of worksheets and homeworks from local primaries, has been pretty shonky.

One example is a text where the students have been asked to underline 9 adverbs in a passage and then “circle the verbs they are describing”. Aside from the issue of saying that adverbs ‘describe’ verbs (which they might do on some occasions, I suppose, but don’t on many others) is a problem about how some of these are classified. Among these adverbs (according to the answer sheet) is ‘within’, which might be seen as a preposition rather than an adverb or (according to my Cambridge Grammar of English, anyway) as a ‘prepositional adverb’; in either case, it isn’t really ‘describing’ a verb at all, is it? Another example (‘almost’) is an adverb but isn’t describing a verb at all, but another adverb (‘entirely’).

I’d be interested to hear what you think of this example, but the wider point – and one which really worries me about the KS2 test and its implications for teaching – is that this is pretty much the only work on grammar my daughter and her class have been doing in Year 6: endless worksheets and drills for the test, rather than the integrated grammar teaching that I would much rather see at this age.

LikeLike

>I know the tests themselves go through a pretty rigorous process of checking (you’re involved, Bas, so I wouldn’t expect any less!) but many of the resources and tests that teachers are using don’t. Some of the stuff I’ve seen, in the form of worksheets and homeworks from local primaries, has been pretty chunky.

Yes, I agree, which is why we developed Englicious (www.englicious.org) a freely available site which uses grammatical terminology as specified in the National Curriculum. What’s more, Englicious aims to teach grammar in a fun and engaging way, and if teachers use it they will avoid the kind of problems that you highlight in your second and third paragraphs.

LikeLike

I also thought ‘running’ was a gerund that forms a compound noun; either way, I agree it’s not an adjective.

As an aside, it’s interesting to note that these –ing forms are falling out of fashion; one sees advertised ‘run vests’ or ‘swim shorts’, perhaps owing to the pressures of space on websites and price tags. It would be even more of a booby trap if these present tense forms were included in the test.

I also thought the term ‘present participle’ was no longer favoured, because it can be used in past tense constructions (‘I was running’). I’m not keen on the terms –ing and –ed participles either (although I notice they are used on the Internet Grammar of English); continuous or progressive participles and perfect(ive) participles seem like better choices – are these used?

And, as someone relatively new to the blog, I’d just like to say how much I enjoy and appreciate these posts, so thank you to you, Bas, for raising these issues and sharing your knowledge.

LikeLike

Dear Steven,

On the gerund, see my reply to Tom above.

Interesting comments on -ing forms falling out of fashion! I wonder why this is happening.

On the term ‘present participle’: yes, many grammarians disfavour this term for the reasons you give. However, I keep using the term (also in my Oxford Modern English Grammar) because it is so widely used. Huddleston and Pullum in their Cambridge Grammar of the English Language use ‘gerund participle’, but I don’t care much for that term. I haven’t seen the labels ‘continuous/progressive participle’ and ‘perfect(ive) participle’ used much, though maybe they are common in ELT.

Thanks for your kind words about my blog.

LikeLike

Pingback: Do-be-do-be-do or why the simplest of verbs can be trickiest to explain – Herts for Learning

I’m not an expert (as I suspect most of you are!) but surely the very fact that even you experts can’t agree what the word ‘running’ is in this particular sentence MUST tell you everything you need to know here? The test was flawed (whether deliberately or not is neither here nor there!) What chance do our little 6 and 7 year olds have (6 and 7!) if you can’t agree?

LikeLike

See my blogpost ‘Right and wrong answers in the grammar test’: https://grammarianism.wordpress.com/2016/05/20/right-and-wrong-answers-in-grammar-tests/

LikeLike